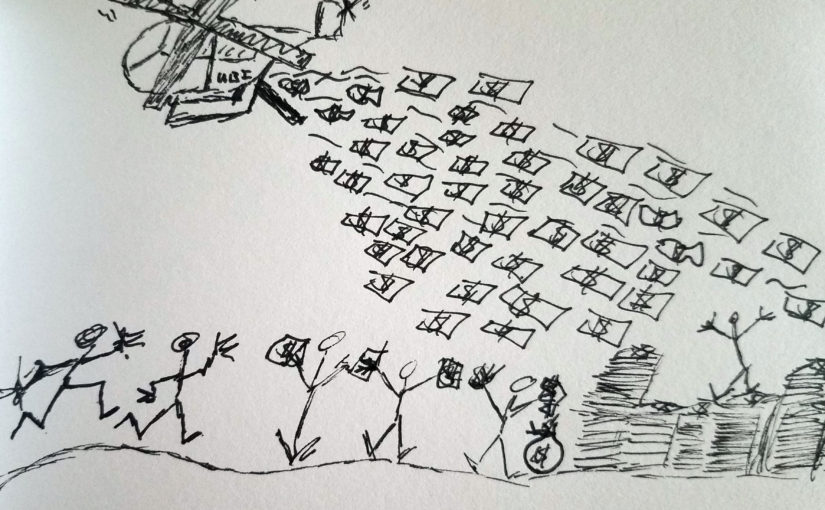

A running list of comments, resources, excerpts and ideas on UBI.

I go back and forth on this topic, and I appreciate the many compelling arguments both for and against UBI.

Most of the stuff out there seems like it’s arguing for the implementation of a UBI and touting its benefits, while there doesn’t seem to be as much content from passionate detractors.

The asymmetry is probably because pro-UBI is kind of the flavor of the month, which attracts front-runners and more popular support. At the same time a lot of the pro-UBI stuff I’ve seen isn’t very compelling.

I used to oppose the idea, mainly for deontological reasons because it could diminish our boot-strapping drive for creativity, growth and innovation, which is arguably already waning in the US.

However, I’m generally pro-UBI these days, primarily because think it would be effective as an optimized social safety net, and big upgrade to our current welfare system.

In that sense, now from a consequentialist mindset, I see UBI helping out a ton of people at the margins — folks who would normally be crushed by a couple bad breaks would now have a useful cushion to help them navigate the turbulence and bounce back from tough times.

I also found Andrew Yang’s argument about using UBI as an incentive to reduce crime and recidivism (noted below) particularly compelling.

At the same time, I don’t think a UBI is the silver bullet: it’s overrated in discussions about how to approach job loss from automation, or more broadly, developments in Artificial Intelligence.

Running list of some arguments against a UBI:

- A UBI will diminish the value of hard work. People benefit from feeling a sense of purpose and reward from their work. If they get money for nothing, they won’t be as driven to work hard to move up.

- People will just spend their UBI on drugs, booze and fast food.

- People won’t be incentivized to get a job and leave the safety net.

- It’s too early. We don’t have enough data to forecast impacts of a UBI. They stopped the program in most places with UBI pilots.

- It’s too expensive.

- Robots will only take our worst jobs, and that’s OK. People will be happier in better jobs eventually.

Running list of some arguments for a UBI:

- A UBI would increase the incentive to stay out of jail, thus reducing crime, incarceration costs and recidivism.

- A UBI would strengthen our social fabric and sense of connectedness.

- Money solves a lot of problems for a lot of people, especially for people at the margins. A UBI could prevent many a downward spiral.

- People will still be driven by intrinsic motivators to work hard and do cool stuff and be creative — most of that drive comes from within rather than from a regular paycheck.

- A UBI reduces the incentive to prove unemployment or disability.

- When robots take our jobs and many are unemployed, a UBI will help enable them to keep buying stuff, thus keeping the economy afloat.

Running list of abstract and half-baked ideas:

- Bundle UBI with a Prize-Linked Savings program for those struggling to integrate back into society.

- Bundle UBI with some kind of mandatory national service to help further strengthen our sense of social connections through shared experiences and productive work and service. This seems like a great blend of intrinsic and extrinsic motivators.

- It’s not useful to compare the results of a UBI study in a developing country to prospects for advanced economies — they’re different worlds with unique benefits and costs.

- We could fund the UBI partially with taxes that send price signals to incentivize strategic behavior that benefits society. For example: congestion pricing, or the Common Ownership Self-assessed Tax (COST) on property from the excellent book Radical Markets.

- UBI would partially fund itself via improved efficiencies in the welfare system, higher consumer spending, higher employment and lower incarceration costs.

- UBI would incentivize work. Rather, it would remove the current counterproductive incentives to prove unemployment or disability to continue receiving benefits. In the current set-up — last time I checked — your benefits are taken away once you start working and making more money. So if I’m struggling and having a tough time keeping a job, my safest path is to keep qualifying for social services and this means keep behaving in a way that helps me prove that I am not working, or prove that I am disabled. With a UBI, you’d make more money, on top of the UBI, if you went out and landed a job.

Running list of resources and references:

- Andrew Yang: The 2020 presidential candidate presents some of the most compelling and level-headed views on UBI I’ve heard. For example:

- Andrew Yang interview with Joe Rogan. I highly recommend listening to every minute of this nearly two-hour interview. Here’s an excerpt: “I was in New Hampshire last month and a prison guard said to me, this is a prison guard, he said ‘We should pay people to stay out of jail because we waste so much money when they’re in jail.’ Like he sees all the waste in the system. So if you imagine a society where everyone’s getting $1,000 a month, that’s like a it’s a great incentive to try and stay out of jail because you know you stop getting it if you wind up in jail and it reduces recidivism because when you come out of jail at least you have you know a thousand bucks waiting for you and then you’re less inclined to commit a crime and head back in.”

- What is a UBI. FAQ about UBI with lots of links to lots of studies, from his campaign website. Here’s an excerpt: “The data doesn’t show [people just spending their UBI money on dumb things like drugs and alcohol]. In many of the studies where cash is given to the poor, there has been no increase in drug and alcohol use. In fact, many people use it to try and reduce their alcohol consumption or substance abuse. In Alaska, for example, people regularly put the petroleum dividend they receive from the state in accounts for their children’s education. The idea that poor people will be irresponsible with their money and squander it seems to be a biased stereotype rather than a truth. Decision-making has been shown to improve when people have greater economic security. Giving people resources will enable them to make better decisions to improve their situation. As Dutch philosopher Rutger Bregman puts it, ‘Poverty is not a lack of character. It’s a lack of cash.’”

- The Finland UBI study: Preliminary results of the basic income experiment: self-perceived wellbeing improved, during the first year no effects on employment

- Jeff Sachs: I really liked this perspective from Jeff Sachs during the Q&A section of his interview on Conversations with Tyler:

- AUDIENCE MEMBER: My question is regarding robotics, potentially — or futuristically speaking — taking over what would be the low-skill jobs at first. What do you think the implications would be on immigration? … On immigration, due to the changing labor market.

- JEFFREY SACHS: Yes, the robots are a kind of immigrant, so they’re competing with the other workers that provide some services that are being replaced by the machines or by the artificial intelligence systems. There is a big distributional effect, in my view. Those who own the robots, as it were, whether it’s Larry Page and Sergey Brin or others, make a fortune. And those who own the labor that is being substituted see a real decline of their income. Again, conceptually, the idea that machines could do the heavy lifting for us is a good thing for society. I don’t know if it’s a real insight or not, but I went to Virunga National Park in Rwanda [sic] a couple of years ago to visit the great apes, the gorillas. You spend this remarkable time in the bamboo forest watching them. What do they do all day? They play. They lie around. They eat some bamboo shoots. A little sex now and then. Basically, it’s a pretty leisurely existence. We’re told, by anthropologists, that that’s not so much unlike hunter-gatherer societies in the pre-Neolithic. We got into a different mode about 10,000 years ago. Became sedentary. Human populations rose. For the next 10,000 years, people broke their backs trying to stay alive growing food. We got into a kind of mode where, basically, very, very, very hard labor. The big quest of modern times is to get out of that hard, heavy physical labor. That’s what everyone in the world wants. As soon as you can get out of agriculture, people do. That’s why we’re down to 1 percent of our labor force in agriculture. It’s very hard work. When you watch people bent over for eight hours in the fields in Africa today, it’s no joy for their lives. It’s extraordinarily difficult.I say all of this because what machines do, what smart machines have been doing for 200 years, is allowing us to ease that physical burden. We’ve had robots for a long time now. They’re just getting smarter and smarter because they have microprocessors now and artificial intelligence. They’re allowing humanity to escape from a very heavy load. On principle, this is a nice thing. This is where we would like to go. If it leads to turmoil, massive inequalities of power and income and wealth, or, by the way, the other dystopian possibilities, which George Orwell depicted…All I’m saying is, like all the things we discussed, I believe that artificial intelligence robotics is real, deep, transformative, potentially for the good, possibly for the bad, and, therefore, a matter of analysis and choice.

- Give People Money, by Annie Lowrey, was too heavy handed and one sided for my liking, which wasn’t necessarily a surprise given the aggressive title. I didn’t think it picked apart the nuances with much depth or balance. This book was recommended by a few prominent economists, so there are probably lots of people smarter than me who liked it. Here are some of the sections a liked, with my notes in bold:

- “If the Luddite fallacy were true we would all be out of work because productivity has been increasing for two centuries.” — Alex Tabarrok, quoted in Give People Money p. 19

- “Even given such painful dislocations, economists see the job losses created by technological change as being a necessary part of a virtuous process. Some workers struggle. Some places fail. But the economy as a whole thrives. The jobs eliminated by machines tend to be lower-paying, more dangerous, and lower-value.” — Give People Money p. 17

- “A UBI need not make an economy more sclerotic, need not divide makers and takers, and need note become a pacifier for the fussing, jobless masses, in other words…One of our best pieces of evidence to this end comes from Iran, of all places.” — Give People Money p. 65 (AF: Iran is not a relevant proxy for forecasting the effects of a UBI in the US.)

- “What we have accomplished is at the very least to shift the burden of proof on this issue to those who claim cash transfers make poor people lazy, and to show the need for better data and more research.” Give People Money p. 65

- “‘There’s tons of discussion and tons of opinion, but almost no factual basis for that discussion,’ Mike Kubzansky of the Omidyar Network said. ‘From our point of view, we need to fact bases: one for wealthy OECD countries like the United States and another for emerging-market countries.’” Give People Money p. 93 (AF: This point touches on many of my issues with the book’s examples.)

- “If robots were to start putting all of us out of work at some point, it might make sense to tax them too — an idea that Bill Gates floated a few years ago. ‘Certainly there will be taxes that relate to automation. Right now, the human worker who does, say, $50,000 worth of work in a factory, that income is taxed and you get income tax, social security tax, all those things. If a robot comes in to do the same thing, you’d think that we’d tax the robot at a similar level,’ he mused to the website Quartz. ‘What the world wants is to take this opportunity to make all the goods and services we have today, and free up labor, let us do a better job of reaching out to the elderly, having smaller class sizes, helping kids with special needs. You know, all of those are things where human empathy and understanding are still very, very unique. And we still deal with an immense shortage of people to help out there. So if you can take the labor that used to do the thing automation replaces, and financially and training-wise and fulfillment-wise have that person go off and do these other things, then you’re net ahead.” Give People Money p.189

- “A broader change in our understanding of worth and compensation, of work and labor, would also be necessary. The neoliberal values of free markets, unfettered competition, and economic growth as the primary arbiters of human progress would need to change. Leisure, comfort, and care would need to become essential to the workings of society rather than being supportive or incidental.” Give People Money p. 208 (AF: This is the wrong way to think about it. We need to value work more, and we need to work harder. Our incentives should be targeted toward building a culture to that works hard and values work. Leisure and comfort are a perk, not the goal.)